"We have got to get inflation behind us. I wish there was a painless way to do that. There isn’t.”

― Jerome Powell, September 22, 2022

In August at Jackson Hole, Wyoming, current Chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve Jay Powell said that the nation’s central bank, “must keep at it until the job is done.” The phrase “keep at it” paid tribute to former Chairman of the Federal Reserve Paul Volcker and his memoir Keeping At It: The Quest for Sound Money and Good Government. In 1979, when Paul Volcker was appointed Chairman of the Federal Reserve, interest rates were historically high, yet inflation was still higher. With its institutional habit of making small, incremental changes to the discount rate, Volcker thought that the Federal Reserve was losing credibility.[1] If inflation is too many dollars chasing too few goods, fewer dollars would mean less inflation; therefore, Volcker decided to directly target the money supply.

Volcker unveiled his new policies during a rare press conference on October 6, 1979, the Saturday before Columbus Day.[2] The Federal Reserve increased the discount rate to 12% and increased deposit reserve requirements as well. Volcker ‘kept at it’ until U.S. Treasury-Bills maturing within ninety days reached yields of 17%. Volcker wanted short-term rates to rise but for long term rates to remain lower, a signal that the market was confident the Federal Reserve could control inflation. Under Chairman Volker, the Federal Reserve eventually raised the federal funds lending rate to 20% to combat inflation that had soared to 13.5%--attributed to a spike in oil prices that pushed the cost of goods up and ignited a persistent increase in consumer prices. Three years later, inflation had plummeted to 3.2%. With this success, the Federal Reserve gradually reduced the federal funds rate, prompting a declining-interest-rate environment that prevailed for the next four decades.

Investor success over the last forty years may have largely been due to this multi-decade tailwind of lower interest rates, a trend that fueled an age of access to cheap capital. This favorable environment has now ended, and investors are confronting an interest rate headwind. Interest rates hit an all-time low in 2008 after the Federal Reserve cut the federal funds rate to zero to rescue the economy from the Great Financial Crisis. From 2009 to 2020, when the pandemic began, the United States enjoyed its longest economic boom in history. This era likely ended this year, with resurgent inflation and higher interest rates. As it’s likely inflation and interest rates will dominate the investment environment for the remainder of the decade, investment strategies that worked exceedingly well might struggle in the years to come.

Having promised to emulate the anti-inflationary footsteps of Paul Volcker, Jay Powell continues to “keep at it.” The potential problem is that Volcker’s world was far removed from that which exists today. There is no worldwide push to increase fossil-fuel production to combat spiking energy prices. Quite the contrary, interventionist politics, green energy transition initiatives and labor shortages characterize today’s energy policy environment. Coupled with the growing movement to “rearm, reshore and restock” domestic manufacturing capabilities, inflation may prove more difficult to tame than expected. Volcker was audacious in his actions against incredible political pressure, but he also benefited from an economy that carried far less debt on its collective balance sheet. While Wall Street continues to eagerly anticipate an imminent shift in Federal Reserve policy, inflationary pressures remain high. After falling far behind the inflation curve following the pandemic, the Federal Reserve has raised the discount rate by 4.25% in only nine months, the sharpest increase in rates in the Federal Reserve’s 108-year history, comparable only to the aggressive actions under the leadership of Paul Volcker in 1980.

Berkshire Hathaway investors readily recognize one of Warren Buffett’s more colorful sayings: "You only find out who is swimming naked when the tide goes out." One never really knows or appreciates the risks companies take until they are tested by adverse conditions. This year’s combination of inflation and rising interest rates have created a perverse environment the multi-decade tailwind of falling interest rates managed to hide. The recent collapse of the cryptocurrency exchange FTX is perhaps a harbinger of the changing investment landscape. FTX’s debacle has exposed just how little due diligence takes place among investors willing to chase the shiniest new object that promises outsized returns.

Sam Bankman-Fried, a thirty-year old MIT graduate known as “SBF,” founded and then subsequently destroyed FTX by placing control of his clients’ money in the hands of a small number of friends with no experience, knowledge, or scruples about how to responsibly manage investment funds. Financial record keeping and reporting at the company were chaotic at best. FTX lost around $2 billion of client funds, not to mention billions of dollars invested in the company’s equity that simply evaporated. Sadly, thousands of clients placed money in the FTX exchange with some putting in their entire life’s savings. One wonders why so many were willing to hand over their livelihood to an operation run by a man-child in shorts who was not accountable to anyone…..but the simple answer is the fear-of-missing-out (FOMO) on potential profits.

While news headlines focused on the losses suffered by retail investors, it is the institutional investors who should be taken to task. Sequoia Capital, a well-known venture capital firm, invested $210 million into FTX. “Due diligence” involved a last-minute Zoom call with Bankman-Fried during which he played the video game League of Legends. During the Zoom call with Sequoia to secure additional funding for FTX, SBF clicked away on his game controller while telling Sequoia that he wanted “FTX to be a place where you can do anything you want with your next dollar. You can buy bitcoin. You can send money in whatever currency to any friend anywhere in the world. You can buy a banana. You can do anything you want with your money from inside FTX.” Hearing SBF’s vision for FTX, Sequoia’s side of the Zoom call grew increasingly excited. “I LOVE THIS FOUNDER,” typed one partner. “I am a 10 out of 10,” pinged another. “YES!!!” exclaimed a third partner of Sequoia.[3]

Despite institutional enthusiasm for FTX, there were warnings. CME Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Terry Duffy recalled his first meeting with Sam Bankman-Fried back in March 2022. Duffy's instincts from years of trading in the pits remain sharp and he instantly pegged FTX as a fraud before the company blew up. Duffy recalled how SBF approached him at a conference and told him that he wanted to compete with CME in crypto trading. Instead, Duffy offered CME’s crypto franchises in exchange for working together, but SBF immediately turned him down. Later that spring, Duffy went to Congress and specifically made claims that FTX had set aside insufficient financial resources to back its proposed direct clearing model for crypto derivatives. Instead of acting on Duffy’s analysis, Congressman Ro Khanna berated Duffy for making false statements.[4]

FTX is only the most recent example of troubled crypto exchanges, but FTX may have kept its problems hidden longer if the U.S. Federal Reserve did not increase the cost of short-term lending rates. Many investors forget that when the easy money spigot is flowing, even outright frauds can be made to look legitimate—it often requires only the smallest amount of monetary tightening to expose the con. While excessive use of leverage turbocharged the cryptocurrency bull market that started in 2020, the tidal wave of liquidity unleashed by central banks in the face of the Covid pandemic also played a major part in this disastrous episode. Between March 2020 and February 2022, the G4 central banks (US, Europe, Japan, UK) added $11 trillion to their collective balance sheet. This liquidity wave swamped not just cryptocurrencies but bond, stock, and commodity prices too.

Fourteen years ago the Federal Reserve launched its quantitative easing initiative in response to the unfolding global financial crisis. That initial announcement, which detailed plans to purchase $100 billion in agency debt and $500 billion of mortgage-backed securities by the end of 2008, preceded similar undertakings that culminated in the pandemic-era, $4.4 trillion splurge spanning March 2020 through early 2022. Interest-bearing assets on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet currently stand at $8.6 trillion, up from less than $1 trillion shortly before Lehman Brothers collapsed in 2008. The Federal Reserve now holds $5.6 trillion in U.S. Treasurys, equivalent to 22.7% of the $24.4 trillion in federal debt held by the public, compared to $476 billion and a 7.4% share, respectively, in November 2008.

How the Federal Reserve will remove such an incredible sum of money from their balance sheet is anyone’s guess, but according to then-Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, there is no need to worry. In a February 2011 testimony in front of the House Budget Committee, Bernanke dismissed any concerns and argued that the then-$2.5 trillion balance could easily be reduced once financial conditions improved: “Federal debt monetization would involve a permanent increase in the money supply to pay the government’s bills through money creation. What we’re doing here is a temporary measure which will be reversed, so that at the end of this process, the money supply will be normalized, the Fed’s balance sheet will be normalized and there will be no permanent increase, either in money outstanding or in the Fed’s balance sheet.”

When Wall Street mixes speculative manias with decades of questionable central bank policies, the result is an investment landscape in which FOMO and a desperate search for yield can lead to disaster. The FTX implosion is what one should expect following a multidecade economic addiction to cheap credit that now confronts rising interest rates. An economic reckoning is inevitable but has been repeatedly delayed because many problems and inefficiencies were papered over by borrowing more money to retire previous obligations with newer and cheaper debt. This tactic works well when interest rates are continually falling. Now that companies can no longer depend on access to cheaper capital, operating losses become a problem. When borrowing costs go up, inefficient and fraudulent companies can no longer mask operating losses. This becomes especially problematic for highly leveraged companies that have enormous debt-service costs.

While many market participants remain concerned about interest rate increases, the true risk may be lack of liquidity. The reduction in the balance sheets of central banks, known as quantitative tightening, combined with the refinancing of government deficits at higher interest rates will drain liquidity from the capital markets. Like the air we breathe, markets take liquidity for granted. After years of monetary expansion, coupled with the FOMO mentality, investors have meaningfully increased their risk profile. In periods of monetary excess, Wall Street considers multiple expansion and rising valuations as normal. Because central bank liquidity became the norm, whenever asset prices corrected over the past two decades, the best course of action was to “buy the dip”. Central banks kept expanding their balance sheets, adding liquidity, and saving market participants from almost any bad investment decision.

Market participants accustomed to monetary expansion without inflation must now navigate a backdrop where central banks will seek to reduce their balance sheets by potentially trillions of dollars. The effects of this contraction are difficult to forecast because traders for at least two generations have only experienced an expansionary environment. Diminishing liquidity is already impacting the riskiest sectors of the economy, from high yield bonds to crypto assets. Eventually, when quantitative tightening truly begins, the crunch will reach the supposedly safer assets. Poor investing habits developed and reinforced over decades will be hard to break.

As Jim Bianco of Bianco Research recently postulated, “From 2010 to 2021, how did one get wealthy in the stock market? Buy SPY and then constantly complain that the Fed was not doing enough to make them rich.” Meaning, the bullish narrative to investing was to complain about how bad the economy was doing to force the Federal Reserve to continuously lower interest rates and increase the size of its balance sheet. Jim Bianco summarizes today’s investment dilemma: “The market is a liquidity junkie, it needs cheap money more than good earnings and growth. Everyone expects a recession, and because of that, everyone expects the Fed to pivot, they'll be cutting rates in the second half of the year, everyone expects that will be falling inflation and will drive stocks higher... transitory never really went away." If stocks rally, then financial conditions ease, but the Federal Reserve can then remain hawkish and the “liquidity junkie” stock market does not get its fix of cheaper money. Cartoonist Bob Mankoff captured this timeless catch-22 dilemma forty-one years ago in The New Yorker magazine.

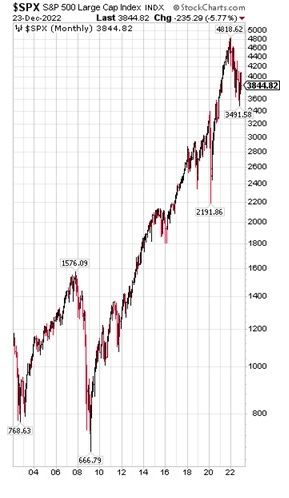

Hope springs eternal and despite 2022’s bruising stock selloff, the market has not yet experienced a wholesale migration out of stocks. To the contrary, investors have purchased a net $86 billion worth of domestic equity mutual and exchange-traded funds in the ten months through October, according to data from Morningstar. This influx marks the second strongest annual inflow going back to 2013, trailing only the $156 billion equity funds received last year. Muscle memory of good times past may explain this resilient urge to buy-the-dip, as the S&P 500 has rallied nearly 500% from its 2009 financial crisis lows. As Jim Masturzo, chief investment officer of multi-asset strategies at Research Affiliates, told The Wall Street Journal, “For the last decade, the U.S. market was ripping every year. Why would people invest anywhere else?”

As markets struggle to accept the fact that the cost for capital has increased, investors will be slow to accept the new investment paradigm. Because valuations have mattered little over the past fourteen years, the current debate between stock market bulls and bears hinges on one’s outlook for inflation, interest rates and market liquidity. This struggle is part of the reason markets suddenly gap higher and then bleed lower – market participants fear missing the next stock move higher should the Federal Reserve “pivot” and lower interest rates. This behavior was readily apparent during the sharp albeit very brief market drops in 2016, 2018 and 2020. However, persistent inflation changes the game, and interest rates at 5% will eventually constrict the life out of untested business models developed over the past decade, dependent on easy money to finance profitless enterprises.

Built up over a decade plus of low or zero interest rates and a simple buy the dip strategy that has left many with no imagination for any other investment other than an index fund, there exists an unfailing optimism in the equity markets. From the moment the stock market peaked in January, Wall Street pundits have downplayed the growing risks within the markets. The day after the market peaked on January 4, 2022, a Bloomberg headline read: “JPMorgan Strategists Say Global Stock Market Party Far from Over.” Every step of the way down, month by month, headlines have bombarded investors with new encouragement that the stock market has reached its lows. Every single buyer of Cathie Wood’s ARK Innovation ETF, a one-stop shop for speculation since August 27, 2017, is now in the red - a classic example of an asset bubble that went wild and subsequently imploded.

Fourteen years of central bank actions shifted risk investor appetites to such a degree that fantastical narratives like ARKK managed to exist. Like all previous bubbles, investors now realize that they were speculating rather than investing and are now facing the consequences. Understandably, all long-term investors need a certain level of optimism to achieve their most basic goal—to preserve and grow the real value of their assets. Inflation can at times make this a high hurdle to clear, but the attempt must be made as the alternative of shunning long-term investment altogether is almost certainly the poorer choice. History has by and large been kind to the optimists and for those intrepid enough to embrace an equity investment approach, but one must also be realistic in their assumptions while maintaining the proper temperament.

Walter Schloss was arguably one of the great value investors of the last century. He pursued a deep-value strategy throughout his career and even offered to buy Warren Buffett's portfolio of stocks when Buffett decided to exit the money management business in the 1960s. In a 1996 speech, Schloss outlined the benefits of value investing compared to any other investment strategy: "We are bargain hunters in the stock market instead of the retail trade or similar areas. As Ben Graham said, we buy stocks like groceries not like perfume, or as they say, 'a stock well bought is half sold.’" Schloss’ primary goal was to avoid losing money, and the best way of doing that was to be contrarian: "When we buy depressed stocks, we seem to reduce our stress. Some people seem to thrive on stress, but we feel in the long run it is bad for them." Schloss told the story of Wall Street legend Peter Lynch, who earned billions for his investors by investing in growth stocks. His approach, however, was extraordinarily time-consuming and required the investment manager to run all over the country finding the hottest companies. After ten years, Peter Lynch quit the business. "I've been managing our fund for 40 years," Schloss noted. "We aren't stressed out yet, and we hope we never will be."

Schloss understood that a value investment philosophy matched his personality. Following the depression in the 1930s, Schloss wanted to ensure that he could always make money and provide for his family. The best way to do this was to limit risk and protect the downside: "Edwin [Walter Schloss’ son] and I look for ways to protect us on the downside and, if we are lucky, something good may happen." Schloss' investment strategy was not complex; a major reason why he was able to compound his investment capital at 15.3% per year for almost fifty years. To invest successfully, Schloss employed a strategy that allowed him to make intelligent decisions while keeping his emotions in check. He understood that how one’s investment portfolio performed in the short term was much less important than how one behaved over the long term. With this mental framework, the investor can have the discipline and courage to act rather than succumbing to the mood swings of other market participants.

No one knows what lies ahead in the capital markets for the coming year. Inflation, interest rates, Federal Reserve policy, earnings, recessions are all beyond the investor’s control. All that one can assume is markets will experience some degree of price volatility. Fortunately, price fluctuations only have one significant meaning for the true investor—they provide the opportunity to buy prudently when prices fall sharply and sell wisely when a stock price far exceeds one’s estimate of fair value. As long term optimists, value investors should stand ready to take advantage of investment opportunities when they present themselves, or as Benjamin Graham said, “The intelligent investor should recognize that market panics can create great prices for good companies and good prices for great companies.”

With kind regards,

St. James Investment Company

[1] The discount rate is the interest rate that the Federal Reserve charges banks for short-term loans. Discount lending is a key tool of monetary policy and part of the Federal Reserve's function as the lender-of-last-resort.

[2] https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/statements-speeches-paul-a-volcker-451/transcript-press-conference-held-board-room-federal-reserve-building-washington-dc-8201

[3] Ethan Gach, “Crypto's Biggest Crash,” Kotaku, November 14, 2022, https://kotaku.com/ftx-crypto-scam-gamestop-token-league-legends-sbf-nft-1849767748

[4] at time 1:57:00