“Every generation laughs at the old fashions but follows religiously the new." -Thoreau.

An American buttonwood tree once stood taller than any other structure on Wall Street. Two hundred and thirty-one years ago, on May 17, 1792, twenty-four merchants signed the Buttonwood Agreement under that tree, establishing the first iteration of the New York Stock Exchange. They agreed that they would only trade with each other and represent the interests of the public, which meant that the confidence they had in each other was the confidence they had in the market.[1]

The Buttonwood Agreement was prompted by the need to establish rules following the 1792 financial panic. British-born financial speculator William Duer instigated the panic by borrowing excessively to trade until he exhausted his ability to borrow. Economic historian Robert E. Wright described the situation, “He was betting that the market was going to go down while everyone else was betting that it was going to go up.” When Duer stopped making payments, concerns arose whether Duer’s lenders would fulfill their obligations. Traders panicked and started selling. The more they sold, the more prices dropped, intensifying the selling — until Alexander Hamilton, in coordination with the First Bank of the United States, stopped the panic.

Brokers signed the Buttonwood Agreement with the aim of restoring confidence and encouraging investment. The War of 1812 ended in 1815, allowing the securities market in New York City to grow. The Buttonwood group added bank and insurance stocks to government bonds as part of the exchange’s trade mix and, in 1817, adopted a new name: the New York Stock and Exchange Board (NYS&EB). In the coming years, the NYS&EB grew, helping New York State issue bonds to finance the Erie Canal. In 1830, NYS&EB traded its first railroad stock, the Mohawk & Hudson. The invention of the telegraph broadened the market’s reach beyond New York City in 1844. The NYS&EB changed its name to the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) in 1863, followed by the completion of the first trans-Atlantic cable, which provided instant communication between New York and London in 1866. Edward Calahan introduced the stock ticker the following year, delivering current prices to investors. The trading room floor received its first telephone in 1878, two years after Alexander Graham Bell’s invention.

By the early 1920s, American economic prosperity and industry boomed. The public wanted to participate in this wealth creation and bought common stock on the open market, often resorting to borrowing money. Market speculation increased as people purchased stock in hopes of future price increases. On Tuesday, October 29th, 1929, the stock market crashed, and more than sixteen million shares changed hands. Stunned brokers on the NYSE watched stock prices plummet so fast that the ticker was four hours behind when the bell sounded at three o’clock. Stock values dropped steadily for the next three years into the Great Depression. The market eventually recovered and has prospered in the decades since. Today, the NYSE is the world’s largest stock exchange, trading over $19 trillion.[2]

Although technology advances relentlessly, human emotions remain the same. Any investor with average intelligence should realize that the best time to purchase securities is when prices are depressed, not inflated. Still, most public buying of securities is done at the top of a significant market cycle, while most selling is done when prices collapse. Greed often accounts for most speculation and lack of discrimination when selecting investments. Greed is also a synonym for impatience. A standard error one makes is projecting present conditions into the indefinite future. Unfortunately, that line of thought can lead to the permanent destruction of one’s investment capital. As investment author Thomas Gibson noted one hundred years ago in 1923, “There is overwhelming evidence that speculative operations conducted in even the best securities on insufficient margins, on erroneous conceptions of values — particularly future values, or in opposition to economic conditions and prospects, will inevitably result in a loss in the long run.”

Despite all the technological advances security exchanges provide today, markets still reflect investor hope and anxiety. Recent experiences significantly influence emotional expectations, and most investors tend to cling to their current path. Generally, market participants base their expectations on the current situation for emotional rather than rational reasons. Instead of maintaining a free and open mind, individuals anchor their opinions, avoiding information contrary to their expectations. The issue is compounded by tendencies to become overly defensive of their judgments – not because they are suitable or likely to be correct, but because they are stubborn.

When challenged by new information suggesting unfavorable consequences or judgmental inaccuracies, most dismiss it as irrelevant to their circumstances. This bias hinders one’s ability to make informed and sound judgments about the future. History thrives with examples of people falling into this fundamental trap. Author Shepherd Mead offered a humorous example in his book “How to Get to The Future Before It Gets to You.” Looking back to 1850, Mead ridiculed city planners studying the developing pollution problems in New York City. The leading causes of concern were chewing tobacco and horses, more precisely, spit and horse manure. In 1850, the spit level in the gutter was half an inch high, and the manure level in the middle of the road also averaged half an inch. By 1860, each had reached a level of one inch. If one modeled prevailing growth rates as a basis of a forecast, levels of two inches were expected by 1870 and four inches by 1880. By 1970, they expected 2,048 inches of spit in the gutters and 2,048 inches of horse manure in the streets, or 170 feet 8 inches each.[3]

Forecasts seldom materialize as expected—they fail to recognize that people will change their behavior before the spit and manure levels reach the second-story window. Stanley Druckenmiller, retired hedge fund manager and former president of Duquesne Capital, explained in an interview how one materially underestimates trend-changing events during the early stages of development. As a young research analyst at Pittsburgh National Bank, Druckenmiller’s first mentor taught him an important lesson: Never invest in the present. Druckenmiller’s mentor taught him that one must visualize the situation eighteen months from now, and the price at that point is where it will be, not where it stands today. Too many market participants myopically focus on the recent trend.

The Wall Street Journal recently detailed the transformation of Spruce House Investment Management, a hedge fund founded by two friends, who shifted their original value investment style to one focused on speculative growth. In college, the fund’s principals consumed Warren Buffett’s annual letters, embracing his value-driven investment philosophy. Spruce House began operations in 2006 as a disciplined value investor, but in 2017, the managers started placing large wagers on high-flying growth stocks. The shift in strategy was initially successful. Unfortunately, by 2022, technology and growth often accounted for more than 70% of Spruce House’s disclosed global public holdings, up from less than 20% in early 2017. The strategy cratered in 2022, and despite robust performance in 2023, the hedge fund is still striving to recover to break even.

The speculative stocks favored by Spruce House faltered when the U.S. Federal Reserve began hiking interest rates and the fund lost about two-thirds of its clients’ money in 2022. Of course, Spruce House is not an isolated example, as many investment funds have been drawn to the huge returns promised by growth stocks since the 2008 financial crisis. Sustained low-interest rates invited risk, as money flowed into fast-growing public and private companies, supercharged corporate valuations, and boosted investor returns. However, venturing beyond their discipline proved disastrous, as chasing shiny growth objects contradicts Buffett’s principle of sticking to what one knows. Having rediscovered their investment value roots, the fund’s managers informed their investors that they were re-examining their portfolio and trying to stay focused and unemotional. Furthermore, they “vowed to return to prioritizing companies that were consistently profitable and carried little debt.”[4]

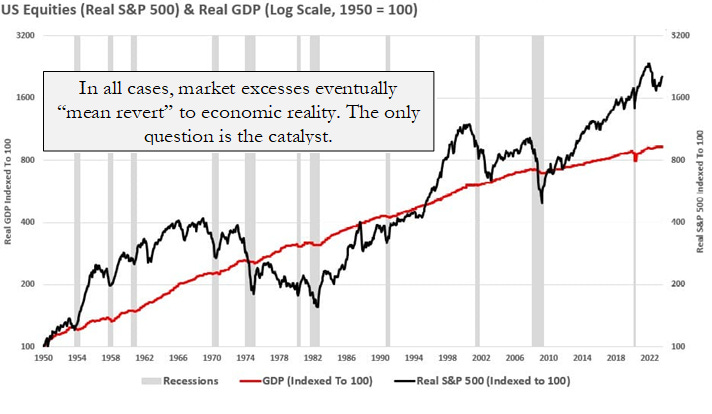

Since 1947, the S&P 500 Index’s earnings per share have grown at 7.7% annually, while the U.S. economy expanded by 6.4% annually.[5] However, following a decade of abnormally high returns, many investors have become complacent and continue to expect elevated rates of return from the financial markets. This complacency is a basis for various justifications to rationalize overpaying for assets.

The gap between fundamentals and valuation may lose significance if policymakers actively support asset prices. Markets can detach themselves from underlying economic activity for lengthy periods as speculative excess separates market prices from fundamental realities. Regrettably, future investment returns may disappoint those who invest based on today’s recent market trends. It is important the investor acknowledges that recent excess returns resulted from a monetary illusion of the “new normal.” Dispelling this illusion may pose challenges for market participants seeking to navigate the potential consequences of a decade of financial distortion.

Predicting when markets will reflect macroeconomic headwinds is impossible. As the adage goes, “In economics, things take longer to happen than you think they will, and then they happen faster than you thought they could.” Eventually, all investors face a significant adjustment — markets will reprice all assets because several vital trends are ending. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, markets embraced a shift towards low and stable inflation. As a result, interest rates fell to levels not seen since the Second World War — a “new normal” had been established. Fiscal and monetary policymakers took advantage of what seemed like a free lunch by pushing interest rates down, priming the economy with tax cuts, and expanding government spending.

Coincidentally, favorable structural forces in the global economy are coming to an end. China’s leaders no longer embrace the forty-year mantra “to get rich is glorious.” In the future, China will emphasize state-led growth, shared prosperity, and national security. After powering global growth for decades, Chinese economic growth is slowing. The result is that fewer financial reserves will be recycled into international markets, and China’s economic contribution to lower inflation will wane. The geopolitical landscape is changing as well. The West won the Cold War, which marked the triumph of liberal democracy. But geopolitical conflict and tensions have returned — from Ukraine to Taiwan and Israel. Greater global competition means bigger budget deficits, which ultimately serves as a powerful inflationary factor.

The implications for investors include the rise in long-term interest rates. For decades, the compensation investors required to buy long-maturing assets trended lower. Low inflation made government debt attractive, and the U.S. Federal Reserve’s monetary policies created a non-economic buyer of this debt. Bonds seemed like the perfect hedge for stocks—every time a risk to the economy emerged, central banks rode to the bond market’s rescue. In hindsight, the “new normal” looks like a unique period of historically depressed interest rates following the 2008 financial crisis. In the future, investors will have to relearn their analytical skills and deploy capital without the benefit of a fiscal or monetary safety net. A sustained higher cost of capital will be a return to what was once historically normal.

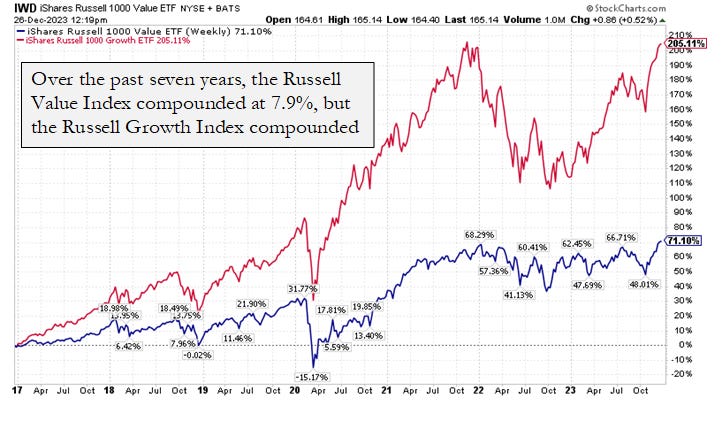

Over the past seven years, the outperformance of growth stocks over value stocks has been nothing short of amazing. Growth benefited from the “new normal” conditions of globalization and central bank financial repression. As Nobel economist Franco Modigliani warned near the 2000 peak, “The bubble is rational in a certain sense. The expectation of growth produces growth, which confirms the expectation that people will buy it because it went up. But once you are convinced that it is not growing anymore, nobody wants to hold a stock because it is overvalued. Everybody wants to get out, and it collapses beyond the fundamentals.” Surprisingly, value performed in line with historical academic expectations. Seven years ago, U.S. Treasuries yielded 2.4%. Add the historical equity risk premium of 5.5% to the starting yield, and an academic might expect an annualized return of 7.9%-- the exact return value generated.[6] However, expected returns and recent price trends can differ materially. Over the long run, any investment will always be a claim on future cash flows. If investors drive prices to extreme multiples of future cash flows, their investment hopes face disappointment.

Like geology, nothing, including speculative growth stocks, is too big to fail. Like speculators chasing recent price trends, the Earth’s crust could theoretically push mountains higher indefinitely. In practice, the scraping of glaciers, the impact of rain, and the constant freezing and thawing of water erode mountains down to size, just as competition and costs reduce a company’s future cash flows. In geology, glaciers are most responsible for limiting a mountain’s growth. However, some mountains manage to escape the erosive effect of glaciers and grow so steeply that glaciers can no longer stick to their sides. With nothing to shave rock off their peaks, high mountains keep growing until their weight is too much for their lower slopes to support, conditions ripe for a cataclysmic landslide.[7]

When allocating capital, investors compare expected returns against potential risks. Horizon Kinetics, a New York-based investment firm, created a simple litmus test in 1999 to compare Microsoft’s earnings with a risk-free rate of return. This exercise aimed to objectively assess how much of the anticipated growth was already embedded in Microsoft’s share price. Horizon wanted to determine whether an investment could lead to success using fundamental guideposts.

To simplify the analysis, Horizon assumed that a pension fund owned all the company’s shares so that capital gains taxes could be ignored. If Microsoft’s market value was $412 billion in February 1999, and all the shares were sold and invested in 5% yielding U.S. government securities, the sale proceeds would generate $20.6 billion of annual cash income. Microsoft itself was projected to earn $6.8 billion that year. If the company continued to grow at its expected 25% rate, the two cash flow streams would equal each other in 7½ years. Microsoft’s cumulative earnings would not match the cumulative Treasury interest income until 2011.[8]

Twenty-four years after the initial litmus test, the market currently values Microsoft at $2.8 trillion, which earns $73 billion annually. Applying the same litmus test, selling Microsoft for a portfolio of U.S. government securities yielding 5% would generate $140 billion of annual cash income. How long before Microsoft’s cumulative earnings exceed the Treasury interest income? What about Apple, with its $3 trillion market value and $96 billion income? Unless the aggressive growth rates under the “new normal” continue, an investment today in Microsoft or Apple under historical norms would prove disappointing at today’s valuations.

The market swoon of 2022 came as a relief for the disciplined value investor. Market behavior finally made sense—inflation drove the cost of capital higher, reducing the value of future cash flows. Over the previous fourteen years, monetary and fiscal policymakers distorted market and economic behavior. Interest rates remained unnaturally low or even negative. The result was an “everything bubble,” a speculative mania in which valuations surged everywhere, from stocks to housing to cryptocurrency assets. The skeptical investor knew that it would never end well and, in 2022, it seemed the return to normalcy had begun. One could have even hoped that investment markets were approaching some level of rationality—a return to reassuringly dull investing—based on fundamentals, not hype.

By contrast, the 2023 stock market has proved confusing. Although interest rates have risen sharply over the past year, stock markets have again climbed within striking distance of all-time highs. The riskiest assets were astonishingly resilient. Bitcoin—once an emblem of the cheap-money era, seen by many as a digital token with no intrinsic value— is indestructible. Asset valuations for select technology and growth stocks have become maddeningly hard to justify. An article in Barron’s Magazine best summed up 2023’s market performance for the skeptical investor:

The failure of the general market to decline during the past year despite its obvious vulnerability, as well as the emergence of new investment characteristics, has caused investors to believe that the U.S. has entered a new investment era to which the old guidelines no longer apply. Many have now come to believe that market risk is no longer a realistic consideration, while the risk of being underinvested or in cash and missing opportunities exceeds any other.

Barron’s published this article in February 1969—times change, but human emotions and behaviors remain the same. Market bubbles reappear throughout history and can thrive longer than a prudent investor’s patience. Rich valuations can grow far more extreme, particularly when investors speculate. In contrast, history provides numerous examples of richly valued markets collapsing without notice once investors suddenly grow risk averse. To navigate markets where many religiously follow the “new normal,” our guiding light remains the old-fashioned definition of investing by Benjamin Graham and David Dodd in their book Security Analysis, published in 1934. “An investment operation is one which, upon thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and a satisfactory return. Operations not meeting these requirements are speculative.”

With kind regards,

St. James Investment Company

[1] Waxman, Olivia. “How a Financial Panic Helped Launch the New York Stock Exchange.” Time. May 17, 2017.

[2] Mystic Stamp Company. “Establishment of the New York Stock Exchange.” https://info.mysticstamp.com/this-day-in-history-march-8-1817/.

[3] Mead, Shepherd. “How to Get to The Future Before It Gets to You.” Hawthorn Books. New York, 1974, p. 15.

[4] Juliet Chung and Peter Redegeair. “A Wunderkind Hedge Fund Strayed Beyond Value Investing. Here’s What Happened Next.” The Wall Street Journal. December 20, 2023.

[5] Lance Roberts. “The Market Is Detached from The Real Economy.” RIA Advice. August 4, 2023.

[6] Equity risk premium refers to an excess return that investing in the stock market provides over a risk-free rate. This excess return compensates investors for taking on the relatively higher risk of equity investing. The size of the premium varies and depends on the level of risk in a particular portfolio. It also changes over time as market risk fluctuates.

[7] “A gigantic landslide shows the limit to how high mountains can grow.” The Economist. July 6, 2023.

[8] Market Commentary: 3rd Quater. Horizon Kinetics. November 2023, page 33.