“Investment success accrues not so much to the brilliant as to the disciplined.“

– William Bernstein

In the 1989 movie Back to the Future II, time travel enables Michael J. Fox’s nemesis, Biff, to become rich by bringing a sports almanac to match outcomes back from the future. Victor Haghani, co-founder of Long-Term Capital Management, thought it might be instructive to replicate a scaled-down version of this scenario. In November 2023, his firm Elm Partners ran an experiment involving young adults trained in finance called “The Crystal Ball Challenge.”[1] Each participant received $50 and the opportunity to grow that stake by trading in the S&P 500 index and 30-year US Treasury bonds with the information on the front page of the Wall Street Journal one day in advance, but with stock and bond price data blacked out. The game covered fifteen days, one day for each year from 2008 to 2022.

The experiment's participants did not perform well despite having the newspaper's front page thirty-six hours in advance. About half of them lost money, and one in six went broke. The average payout was just $51.62, indistinguishable from breaking even. Anyone can now play this game on the company’s website; over 8,000 people have tested their skills (or luck) in the “Crystal Ball” game. Players begin with an imaginary $1 million cash position and are shown fifteen Wall Street Journal front pages following big economic news randomly selected over the past fifteen years. With up to fifty times available leverage, multiplying their initial stake sounds easy. It is not—many players lose their entire stake. Their median ending wealth is just $687,986, according to data provided by Elm Partners.[2]

Wall Street richly compensates an army of economists and market strategists to produce forecasts ahead of market-moving economic numbers. They are often wrong, including the 400 PhD economists at the U.S. Federal Reserve who failed to forecast inflation despite the rapid expansion of the money supply by trillions—only to dismiss it as "transitory." As we approach 2025, Wall Street anticipates the S&P 500 reaching 6,800 by the end of 2025, driven by corporate earnings growth and advancements in artificial intelligence. Morningstar reports that the most optimistic forecast predicts the S&P 500 will attain 7,100 in 2025, citing technological innovation and favorable economic policies. Wall Street has institutional reasons to be bullish, but even Wall Street strategists have been surprised by the market’s current performance. In January 2024, strategists expected the U.S. index to be flat for the year but repeatedly raised their estimates as the S&P 500 powered higher.

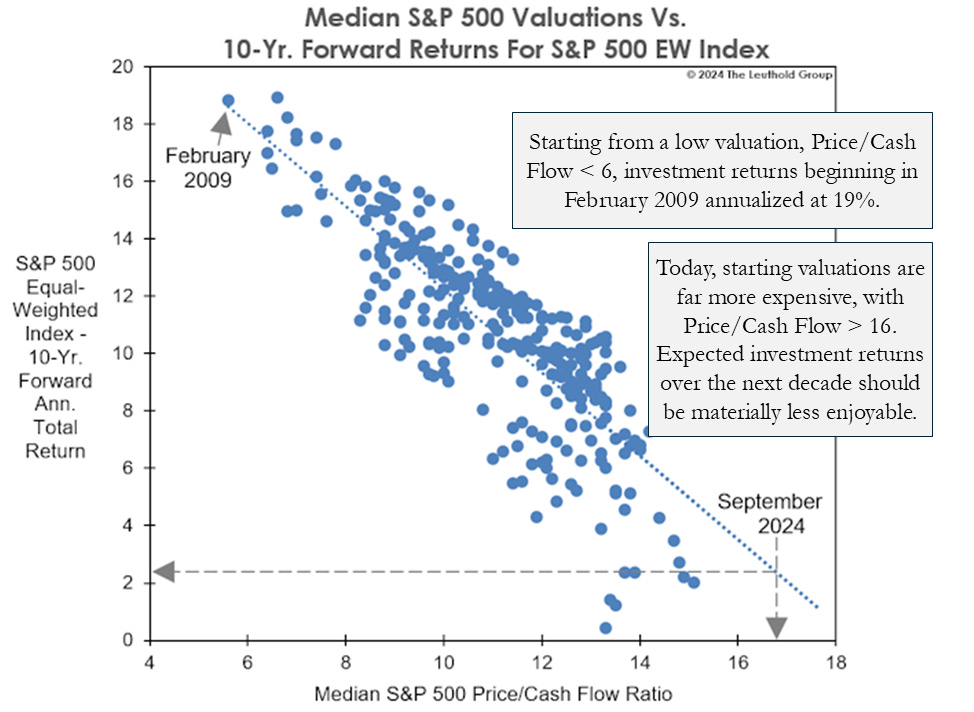

Markets, as John Maynard Keynes famously described, are driven by “animal spirits” - the collective emotions and behaviors of crowds. This inherent instability stems from human nature, where spontaneous optimism often overwhelms rational expectations. In the short term, prices surging in a bullish trend can create significant momentum, making it challenging to oppose the market's direction. Today’s enthusiasm for the stock market is palpable, with individuals significantly increasing their portfolio allocations to equities. The market's strength fuels a positive feedback loop, as optimism that stocks will continue to rise intensifies as the S&P 500 rallies. However, in the long term, nothing outweighs the importance of valuations. The higher prices climb without an appreciation in fundamentals, the lower expected investment returns one will likely receive over the next decade.

For value investors, this inverse relationship holds little utility in the short term, as it consistently fails as a tool for market timing. Even as an irrationally expensive market grows even pricier, the prudent value investor recognizes that the connection between starting valuations and future returns remains historically sound.

The chart above uses the S&P 500 equal-weighted index rather than the traditional S&P 500 market capitalization-weighted index. In the standard S&P 500 Index, companies are weighted based on their market capitalization, meaning larger companies have a greater influence on the index's performance. In contrast, an equal-weighted index weighs every stock equally, regardless of the company's size. Therefore, Apple, the most significant component of the market capitalization index with a weight of 7.63%, will have the same impact as the smallest company that is a constituent of the S&P 500, News Corporation, at 0.007%.[3] Distortions can and do arise in the S&P 500 index, where just 24 companies account for half of its market capitalization.

When a significant amount of capital flows into passive funds, this inflow is spread across all the stocks in the index, regardless of the fundamental value of individual companies. This leads to stocks priced according to their weight in the index rather than their intrinsic value. These passive flows create price distortions, with stocks that may be overvalued (because of their size or popularity) receiving more fund inflows than warranted based on fundamentals. Similarly, underperforming companies in the index receive more investment than they deserve simply due to their index inclusion. Because passive investing strategies are designed to replicate the performance of an index, they often lead to herding behavior where large numbers of investors buy or sell the same stocks in a coordinated manner. In a market dominated by passive investing, stock prices are less influenced by fundamental analysis (such as earnings, management quality, and growth potential) and more by the inflows into indices. Valuation is ignored when passive funds buy stocks to mirror an index, causing stocks to trade at prices that do not reflect intrinsic value.

The current display of animal spirits among leveraged exchange-traded products is a remarkable sight. According to Bloomberg, the total daily trading volume among single-stock ETFs reached $86 billion recently, the largest figure on record. While speculators enjoy bitcoin’s surge to $100,000, a pair of leveraged exchange-traded vehicles tracking MicroStrategy has attracted enormous fund inflows. MicroStrategy originally started as a business software company in 1989 but has morphed into a leveraged bitcoin speculation vehicle. Two leveraged MicroStrategy ETFs now manage $2.6 billion in assets and have surged nearly fourfold since election day. MicroStrategy is set to join the Nasdaq 100 index, and this is where the story gets interesting.

The Nasdaq 100 comprises one hundred of the largest nonfinancial companies in the technology-focused Nasdaq Composite index. The Nasdaq changes the constitution of the Nasdaq 100 index annually, with companies selected for inclusion based primarily on the company's size on the last trading day of November. MicroStrategy’s addition to the index means that exchange-traded funds, including the popular Invesco QQQ Trust, which has $325 billion in assets, will automatically buy MicroStrategy’s stock regardless of valuation. The market’s massive shift into passive index funds drives an inelastic bid for whatever stocks are in the underlying passive indices. Including MicroStrategy in the Invesco QQQ Trust will presumably drive MicroStrategy’s valuation to further extreme levels. According to FactSet, the company has a market value of $90 billion despite having less than $500 million in revenue over its previous four quarters. Michael Saylor, the company’s CEO, told CNBC’s Squawk Box that he sees the company’s role as “securitizing bitcoin.”[4]

If one is confused by the term “securitizing bitcoin,” they are not alone. MicroStrategy intends to continue issuing a combination of convertible bonds and equity to buy Bitcoin, which has a finite supply of only twenty-one million coins ever to be mined. Just over twenty million Bitcoins have already been mined, most of which have never been traded. Unlike the Hunt Brothers’ efforts in 1980 to corner the silver market, Bitcoin does not have a centralized exchange that authorities can “turn off.” And unlike the silver industry, no mines are ready to expand silver production in response to spiking prices. The combination of leverage, limited supply, inelastic bids, and rampant speculation provide the perfect ingredients for the age of “financial nihilism.”

Travis Kling of Ikigai Asset Management, a cryptocurrency hedge fund, explained that financial nihilism questions the traditional financial system when living costs are strangling most Americans.[5] The opportunity for upward mobility exceeds the reach of increasingly more people—the American Dream is a concept of the past. The underlying driver of financial nihilism is that the system is not working for the average person, so they want to try something different. Baby Boomers purchased their houses at 4.5x their annual income. The government’s enormous response to COVID-19 generated a wave of liquidity that propelled all asset prices higher—the median house now sells at a multiple of 7.5x median household income. Homeownership is now out of reach for millions of Americans under forty. In 1963, the median household income purchased 94 shares of the S&P 500 index. That number peaked at the market bottom in 1982, when the median household income purchased 219 shares of the S&P 500. Today, the median household income can only purchase 18 shares of the S&P 500.

Financial nihilism completely disregards downside risk because “you only live once.” If one does not take excessive risks, one will never achieve the same lifestyle as generations before. The stock market is less affordable for the average Millennial, and the Boomer generation has all the money. As the “Everything Bubble” inflates all asset prices, the rich who own assets grow richer while the wage-earning poor grow poorer. Americans take greater risks with limited financial means to compensate for this financial asset mismatch.[6] The individual investor feels compelled to take more risk to escape their current financial position, living paycheck to paycheck with no hope of buying a home while saddled with student loans. As Travis Kling summarized, “A dopamine-seeking bubble fueled by years of cheap money and low energy costs has melded with a callous disregard for negative consequences. The roots of this nihilism run deep through a lack of real median wage growth and its populist backlash. Blame decades of bailouts by authorities… You will own nothing and be happy.”

Financial nihilism is not limited to the United States. With continued faith in U.S. financial market strength and capacity to outperform other economies, global investors are pouring more capital into a single country than ever in modern history. The disconnect between U.S. stock prices and the rest of the world is at its highest since data began over a century ago. The U.S. accounts for nearly seventy percent of the global stock index, up from thirty percent in the 1980s. Awe of “American exceptionalism” has driven the U.S. global stock market share far above the country’s twenty-seven percent share of the global economy. Ruchir Sharma, Chairman of Rockefeller International, noted that while traveling in Asia and Europe, he repeatedly encounters investors drawn to the United States. In Mumbai, observed Sharma, financial advisers press their clients to diversify away from India by buying the one market in the world that trades at even more expensive valuations—the United States. In Singapore, Sharma recalled the host of a lunch with wealth managers asking the group, “Anyone here who does not own Nvidia?” Not a single hand went up.[7]

Investors want to believe that fundamentals drive prices and sentiment. Today, it appears that sentiment drives fundamentals. Most attribute the stock market rally to a narrative about future economic growth and increasing earnings. Everyone thinks they are geniuses because the prices of their assets are rising, but easy fiscal and monetary policies also drive prices higher. Aggregate U.S. government spending far exceeds tax revenue received. The U.S. government funds this deficit by borrowing money through debt issuance, primarily in the form of Treasury securities. Deficit spending that exceeds the economy’s productive capacity is inflationary. If the government borrows from the Federal Reserve, deficit spending increases the money supply, which is also inflationary. If individuals believe that the government will continue running deficits and that the central bank will "monetize" that debt, expectations of future inflation will solidify.

The standard view that inflation is "higher prices" rather than a devaluation of the dollar comes from how inflation is traditionally measured. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) tracks the average price changes of a basket of goods and services over time, while most economists typically define inflation as a general rise in the price level across an economy. The simple truth is that the good or service one purchases remains the same; it just takes more dollars to purchase. In 1975, the average haircut cost $5; today, the average haircut costs $25. Nominal dollars measure a dollar's value in the year it is received or spent, unadjusted for inflation, while real dollars adjust for purchasing power. Investors seldom separate rising nominal asset prices from falling real dollars. Asset prices, in general, and stocks, in particular, have risen relentlessly without most understanding the mechanics.

The United States historically operated under a gold standard, where the amount of money in circulation was tied to the amount of gold held by the central bank. Governments or central banks could only issue as much currency as backed by gold reserves. Since the money supply was tied to gold reserves, the government could not operate a budget deficit in perpetuity. President Nixon closed the “gold window” on August 15, 1971, and announced that the dollar would no longer convert into gold. The gold standard was scrapped in favor of what Jim Grant, editor of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, calls “the PhD Standard.” In Grant’s classic manner of speaking:

“One can think of the original Federal Reserve note as a kind of derivative. It derived its value chiefly from gold, into which it was lawfully exchangeable. Now that the Federal Reserve note is exchangeable into nothing except small change, it is a derivative without an underlier. Or, at a stretch, one might say it is a derivative that secures its value from the wisdom of Congress and the foresight and judgment of the monetary scholars at the Federal Reserve. Either way, we would seem to be in dangerous, uncharted waters.”[8]

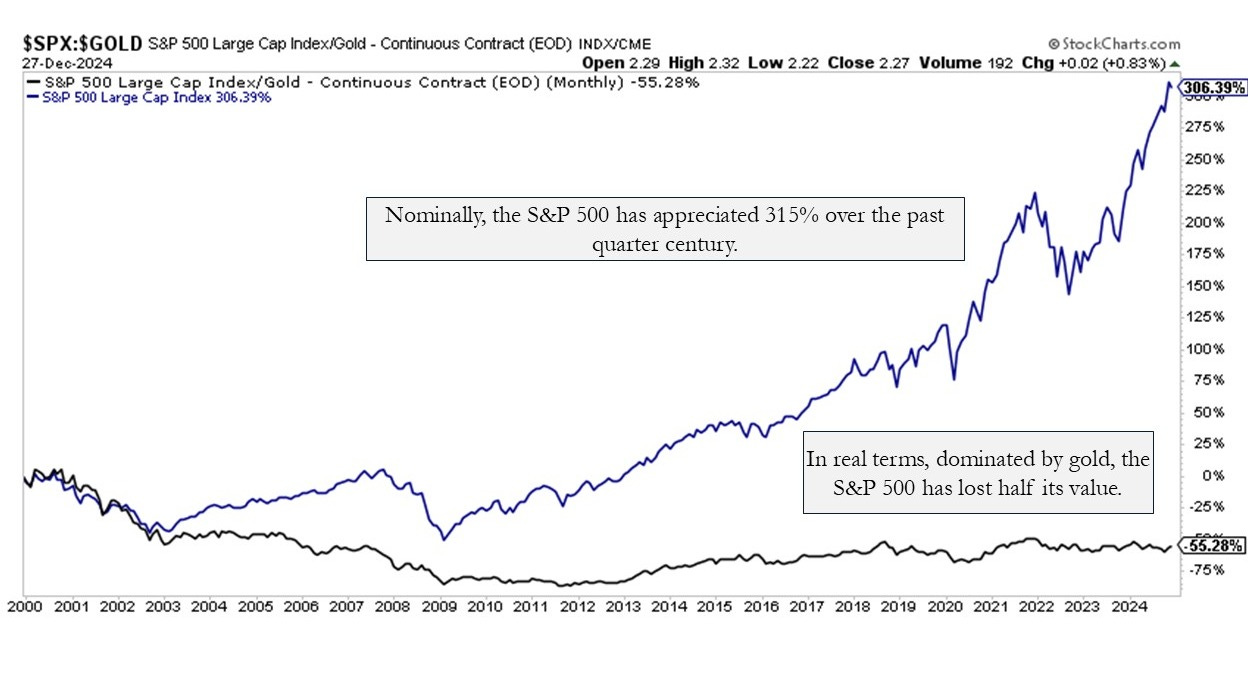

Throughout history, politicians have succumbed to the temptation to fund the spending desires of their citizens by diluting their purchasing power. In the past five years, the combined impact of fiscal stimulus (direct spending, tax relief, and aid programs) and monetary stimulus (quantitative easing and liquidity programs) has added almost $10 trillion to the U.S. economy. While the S&P 500 index has nominally doubled over the past five years, it has barely risen in terms of gold, a real asset. Over the past twenty-five years, U.S. national debt has increased from $5.6 trillion to $36 trillion, and the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio has risen from 60% to 120%. Nominally, the S&P 500 has appreciated 315% over the past quarter century.

In real terms, dominated by gold, the S&P 500 has lost half its value, something speculators should consider as they pat themselves on the back for their trading performance. Wall Street justifies nominal performance by endlessly talking about fundamentals, earnings growth, and favorable macroeconomics, but a continuously devalued dollar hides risks that can trap complacent bulls. Overconfidence in America’s economic position and financial asset inflation without accounting for the falling real value of the U.S. dollar carries its own risk. Dollar debasement is one reason to invest in U.S. equity markets today, and it will remain so until it is not. As with all bubbles, it is impossible to know when this one will deflate or what will trigger its decline.

A fundamental truth about investing is that one cannot invest in the market one wants; one must invest in the market as it currently exists. Reality, rather than idealized or desired conditions, shapes the investment landscape. An investor must navigate today’s market realities, whether dealing with volatility, inflation, absurd valuations, runaway government spending, or a debasing currency. Almost six decades ago, a generation of investors cut their teeth in an inflationary environment with double-digit interest rates, low price-to-earnings multiples, and a market that went nowhere for sixteen years. The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) started near 1,000 in January 1966, but the nominal index level experienced significant volatility over the following sixteen years and ended near 1,000 in December 1982. Adjusted for inflation, the DJIA fell by 70% in real terms. None of the lessons learned during that lost decade and a half helped the investor navigate a far different environment from 1982 to 1999, where the DJIA increased by over 1300%, and inflation steadily decreased.

Confronted by a concentrated market structure with a relentless passive bid, low interest rates, massive corporate share buybacks, and the reality that valuations hold little significance in the financial markets other than during brief periods of credit stress, the value investor struggles to participate. And while the nihilism of the many individual and corporate price setters cannot be overlooked, opportunities still arise away from the herd. For investors who accept current market conditions but remain committed to fundamentals, realism and patience are essential. This approach involves acknowledging personal constraints that limit participation in today's market darlings while focusing on the universe of overlooked, high-quality companies with compelling valuations.

John Templeton, a pioneer in global investing and contrarian strategies, developed an investment philosophy centered on disciplined research and focusing on long-term value. He started his investment career in 1939 and bought a small investment firm that became Templeton, Dobbrow & Vance, the early foundation of his empire. His investment philosophy stands the test of time as one investment era morphs into another. Seventy years ago, in a letter to his investors, Templeton summarized his simple but profound approach – an approach that remains applicable in today’s market environment: “When stocks prices are very low, as they were five years ago, then of course it is wise to have a heavy proportion of common stocks. When prices are very high, as they were in 1929, then of course it is wise to hold only a minimum of common stocks.”[9]

With kind regards,

St. James Investment Company

[1] https://elmwealth.com/crystal-ball-challenge/

[2] Jakob, Spencer. “Would a Time Machine Make You a Great Investor?” Wall Street Journal, October 14, 2024.

[3] https://www.ssga.com/us/en/institutional/etfs/spdr-sp-500-etf-trust-spy

[4] https://www.cnbc.com/2024/12/13/bitcoin-proxy-microstrategy-to-join-the-nasdaq-100-and-heavily-traded-qqq-etf.html

[5] Kling, Travis. “Financial Nihilism” Epsilon Theory. March 12, 2024.

[6] The expression "everything bubble" refers to the correlated impact of monetary easing by the Federal Reserve, followed by the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan, on asset prices in most asset classes, namely equities, housing, bonds, many commodities, and even exotic assets such as cryptocurrencies. The policy itself and the techniques of direct and indirect methods of quantitative easing used to execute it are sometimes referred to as the Fed put.

[7] Sharma, Ruchir. “The Mother of All Bubbles” Financial Times. December 1, 2024.

[8] Grant, James. “A Piece of My Mind,” Speech given to the New York Federal Reserve, 2012.

[9] Templeton, John. “The Templeton Letter,” Templeton, Dobbrow & Vance, Inc., July 29, 1954.