“The key is not to predict the future but to prepare for it." - Pericles

In 1654, scientist and philosopher Blaise Pascal famously wrote: “All of humanity's problems stem from man's inability to sit quietly in a room alone.” A recent study in the journal Science found that many people choose to self-administer an electrical shock rather than endure a period of quiet solitude.[1] While our inability to be alone with our thoughts may not be the root cause of all problems, the study reveals that humans struggle with it, at least under the circumstances the researchers tested.

The researchers assembled a group of students in their laboratory and instructed each participant to sit alone in an empty room for ten to twenty minutes. They removed all distractions, including cell phones, watches, and books. A nearby button was pointed out, which, when pressed, would administer an electrical shock. To familiarize the participants with the shock, the researchers had each participant press the button and then asked whether they would pay money not to be shocked again. The participants said the shock was unpleasant, and they would pay to avoid the unpleasant experience.

The researchers then asked the test subjects to sit with their thoughts for ten to twenty minutes. There were only two rules: they could not leave their chair or fall asleep. They encouraged the participants to enjoy themselves with pleasant thoughts. Lastly, they informed the participants that if they would like to receive an electric shock again, then they were free to press the button. The research team debated this aspect of the study. It was ridiculous to think that people would choose to shock themselves willingly, but the results astounded the researchers. At the end of the study, they found that about seventy percent of the men and twenty-five percent of the women chose to shock themselves during those twelve minutes instead of just sitting and entertaining themselves with their thoughts.

Because university studies often start with college students, the researchers wondered if their young subjects were overly restless and not allowed to tweet, text, or check e-mail. They broadened their search for volunteers and got the same results. These were adults, and the researchers had them sit in their homes without the shock but asked them to do the same thing: sit there at a time of their choosing, when they were alone, and entertain themselves with their thoughts for ten to fifteen minutes. Once again, the test subjects were terrible at it. Over half of the participants confessed to cheating. They were not supposed to get on their phones or talk to others, but over half said they had. The researchers found that people simply cannot sit alone. It is not that humans can never enjoy thinking, but something about doing it on command, at a particular time, and deliberately is difficult.

Kyle Klett, a 31-year-old unemployed poker player, is a prime example of a man's inability to sit quietly in a room alone. Mr. Klett revealed he has endured large losses over the past two years, including a string of mistimed one-day options that cost him tens of thousands of dollars. Still, he said, the big wins have enticed him to keep trading. While participating in the World Series of Poker in Las Vegas, Klett said he “scooped up more than 300 contracts” that would pay off if the S&P 500 index rallied the next day. After he spent a sleepless night checking the futures market, he said the S&P 500 rose 1.2% the next day, and he made $71,000. He celebrated the big win by playing roulette and slot machines while hopping from casino to casino on the Las Vegas Strip. “I lost $25,000 in poker but smoked the market,” he said. Klett said he places around eight options trades daily and typically does not hold them for more than seconds or minutes. Despite the emotional and financial difficulties, Kyle remains emboldened by his recent wins. “I’m just exceptionally great at it,” he said.[2]

Trading volume continues to dramatically increase in options that expire in as little as a day or sometimes just hours. For a small upfront fee, speculators (not to be confused with investors) have the chance for a big payout almost immediately. Market participants cannot sit still with their thoughts—they feel compelled to act. As with the lottery, the downside of this behavior is getting back zero, which is often the outcome. Options enable traders to leverage their bets on individual stocks by getting the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell shares at a set price by a stated date. Shorter-dated options, expiring in five or fewer days, accounted for half of all options-market activity as of August, according to data provider SpotGamma. Individual investors made up around one-third of all trades for popular one-day options tied to the S&P 500 index. This is not investing but instead gambling, or the equivalent of self-administering an electric shock out of boredom.

This year's gains in the stock market have further stoked interest among individual investors in options, enabling them to make short-term, high-return wagers on stocks continuing to move higher. Stock-price movements can cause options values to rise or fall much faster than the underlying stocks' values. Trades that expire the same day can offer the fattest rewards—and carry the most significant risks. Shorter-dated options bets have become so popular they have a nickname, 0DTE, shorthand for zero days to expiration. In our opinion, the pervasiveness of this activity is not characteristic of well-functioning, stable markets.

Peter Bernstein, the well-respected founding editor of The Journal of Portfolio Management, often wondered what investors meant by "investing for the long term". He concluded that "long term" is in the eye of the beholder. For those investors plagued with monthly measurements, a year is the long run, and possibly three years is the absolute limit. The long run is the indefinite future for strict fundamental investors discounting future cash flows. Most investors fall somewhere in between. Each investor defines the long run with a different period in mind, meaning one’s timeframe will be appropriate only by coincidence with another investor. But as Bernstein said, “There is more to the long run than shutting one’s eyes and hoping that some great tidal force will bring the ship home safe, sound, and laden with just the right merchandise for the occasion.”

Berstein approached this question from two different viewpoints. First, he explored whether investing can even exist in the long run. Second, assuming that one can identify and define the long run, Berstein demonstrated that moving from the short to the long run transforms the investment process in far more profound ways than most people realize. When people talk about the long run, they mean that they can distinguish between the signal and the noise. Yet the world is a noisy place. “Discriminating between the main force and the perpetual swarm of peripheral events is one of the most baffling tasks humans must confront and can never duck.” Berstein rhetorically wondered if the championship baseball team losing three games in a row signals the beginning of the end of their league dominance or a brief interruption in their string of victories. When the stock market drops ten percent, is that the beginning of a new bear market or just a correction in the ongoing bull market?

Long-term investors believe they can distinguish signal from noise and scorn traders who are too busy chasing lines on charts. The long-run investor faithfully believes in "regression to the mean." In the long run, everything evens out as the main trends dominate, or so think much of the active investment management community. "Undervaluation" or "overvaluation" implies some identifiable norm to which values will revert. Other investors may choose to succumb to fads and rumors, but investors who persist will win out in the long run. Or will they, wondered Bernstein? The lesson of history is that norms are never normal forever. Times change, and paradigms shift; perhaps so has the concept of regression to the mean.[3]

John Maynard Keynes, an astute investor who knew a few things about economics, took a dim view that one can look through the noise to find the signal. In a famous passage, he declared, "The long run is a misleading guide to current affairs. In the long run, we are all dead. Economists set themselves too easy, too useless a task if in the tempestuous seasons they can only tell us that when the storm is long past, the ocean will be flat.” Keynes believed that tempestuous seasons are the norm. The ocean will never be flat soon enough to matter. Keynes believed equilibrium and central values are myths because we can never escape the short run.

How one feels about the long run and how one defines it are gut issues for the investor. These concerns are resolved more by the nature of one’s philosophy of life than by rigorous intellectual analysis. Those who believe in the permanence of tempestuous seasons will view life as a succession of short runs where noise dominates signals. Those who live by regression to the mean expect the storm to pass so that the ocean will be flat one day. Experience teaches us that chasing noise leads one to miss the primary trend too often. At the same time, the investor should look suspiciously at all main trends and all those means to which variables should regress. According to Bernstein, the primary task in investing is to test and then retest the parameters of the current paradigm that appear to govern daily events. Betting against them is hazardous when they look solid, but accepting them without question is perhaps the most dangerous action.

In a recent conversation, James Tisch, the President and CEO of Loews Corporation, presented his views on the current market paradigm and its implications for investors. As early as 2011, Tisch sensed that the Federal Reserve should begin raising rates above zero to get the markets accustomed to paying some amount to borrow money. Instead, markets and governments became accustomed to zero money market rates and unsustainably low term rates. “The Fed’s assets, which amounted to less than $1 trillion before the 2008 financial crisis, ballooned to nearly $4.5 trillion by the end of 2014. The Fed’s balance sheet remained around $4 to $4.5 trillion until the outbreak of COVID in early 2020. During COVID, the Fed’s balance sheet more than doubled to nearly $9 trillion. Despite recent quantitative tightening, the Fed’s balance sheet is still more than $8 trillion, more than eight times its size prior to the Great Financial Crisis.” To the disappointment of speculators paying zero, if any, interest on debt, today’s market paradigm has shifted meaningfully. Going forward, markets are returning to the days of real interest rates [interest rates higher than the inflation rate] for the U.S. Treasury and other issuers.

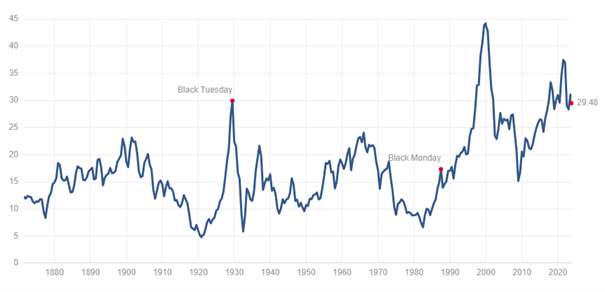

The current investment paradigm is that the U.S. government runs an operating deficit of -6.3% of a fully employed economy. This has never happened before. Over the past six decades, the U.S. government operated with mild deficits at barely over 1% of the economy—today, the ratio is six times higher, with a 3.6% unemployment rate. Should the unemployment rates move higher, one can only imagine where that deficit/GDP ratio goes if the Federal Reserve achieves its goal of a 4.5% unemployment rate. Wall Street “experts” tell us to ignore expensive valuations even though they represent what investors pay for future earnings. The Shiller PE multiple currently sits just below a multiple of thirty compared to the long-run norm of eighteen. Despite an expensively valued stock market, coupled with year-over-year earnings per share down 7.3%, the S&P 500 has rallied nearly 20% in 2022. The math does not compute in today’s new investment paradigm other than to indicate anything more than a speculative momentum-based rally.

The United States comprises roughly 4% of the global population, but today's U.S. budget deficit is 40% of the world's budget deficit. Within today’s investment paradigm, to keep the United States government operational, it must attract over one-half of the world's marginal increase in savings year in and year out. If the United States cannot draw this amount of global savings every year, then there will be a problem with the country’s sovereign debt or a problem with the U.S. dollar. The Federal Reserve’s actions to address these issues will almost certainly prove inflationary. That is the new paradigm that investors must consider. The ramifications are important. John Maynard Keynes wrote: “As the inflation proceeds and the real value of the currency fluctuates wildly from month to month, all permanent relations between debtors and creditors, which form the ultimate foundation of capitalism, become so utterly disordered as to be almost meaningless; and the process of wealthgetting degenerates into a gamble and a lottery.” For the modern investor, the concept of “normal” is delusional: a stock index that keeps going higher. That is the beginning and end of his understanding of anything “normal.” He or she only knows what has worked in the past: more monetary accommodation means higher stock prices.

Investors often assume that extreme valuations imply that stock prices should fall. Therefore, if stock prices do not fall, the valuation measures must be incorrect. Valuation analysis does not operate in that manner—valuations provide information regarding expected long-term investment returns and the extent of potential losses over the complete market cycle. Valuations provide minimal insight into market direction over short periods within the market cycle. If rich valuations were sufficient to pressure stock prices, stocks would never reach valuations observed in 2000, late 2021, or today. Study any period in history where fundamentals grew and market valuations increased, and one finds that total returns were high during that period, regardless of how rich starting valuations might have been. Likewise, find any period in history where market returns were materially higher than they “should” have been, given the level of starting valuations, and one will find that the period ended at extreme valuations. 2000, late 2021, and today provide three prime examples of this dangerous position.

No matter the cause of a speculative bubble, bleak long-term investment returns tend to follow all valuation bubbles. At current market valuations, history suggests that investors should expect S&P 500 total returns to underperform U.S. Treasury bonds for many years. Rich valuations can become even more exaggerated, particularly when investors wish to speculate. However, these lofty valuations collapse when investors become risk averse. On a total return basis, ten-year U.S. Treasury bonds have lost over -22% since late-2020, while thirty-year U.S. Treasury bonds have lost -45%. Counterintuitively, those losses have improved the prospects for future returns, unlike the equity market, where the S&P 500 remains near the most historically extreme valuations.

Investment success is often characterized exclusively by return without consideration for risk management. Investment returns are readily quantifiable, while risk cannot be easily measured. Although one can observe what happened, one can never accurately measure how much risk was incurred. When investors measure investment risk, they typically assess the historical volatility of an investment compared to that of the overall market. This measure is irrelevant because volatility differs from risk, and one cannot reliably project past share price patterns into the future. By contrast, the value investor adheres to a more practical view of risk—how much can be lost and the probability of losing it. While this perspective may sound outdated, it clarifies the actual risks of investing.

Most professional investors face significant pressure to generate returns in the near term. They believe their clients demand it, and often, their internal incentives encourage it. Few investors are comfortable taking a truly long-term point of view, no matter how compelling the opportunity, as results are measured in the short run. While others attempt to win every lap around the track, it is crucial to remember that to succeed at investing, one must finish the race. What matters is not who performs best during sequential short-term intervals but rather who attains a reasonable, long-term, risk-adjusted, cumulative result. Strangely, risk moves to the forefront of investor consciousness only when markets are going down. Losing money is the only thing that makes most investors worry about losing money. With so much pressure for competitive short-term performance, worrying about what can go wrong may seem like a luxury. Paradoxically, when almost no one sees markets at risk, even a minor increase in investor perception of risk can trigger dramatic market declines.

While worrying about what can go wrong is crucial, one should differentiate between productive and unproductive worrying. Unproductive concern will not and cannot make a difference. Worrying that your favorite football team may lose is unproductive. By contrast, productive worrying enables one to identify actions that reduce or eliminate the source of concern, often at little cost. If one worries about arriving late for an appointment, leave earlier than planned. By avoiding loss, investors maintain what they have accumulated, the foundation of successful investing. None of us can see ten years ahead. All the investor knows with some degree of certainty is that our current world is ripe with potential for extraordinary change: financial, economic, and geopolitical.

Pericles was an ancient Greek politician and general who played a crucial role during the Golden Age of Athens. A senior Athenian statesman and general of the Peloponnesian War, Pericles led Athens with a genius understanding of the nature of strategy that contributed significantly to the growth of the Athenian Empire. Sparta, the main rival to Athens, despised the Athenian democratic way of life and feared the threat posed to their independence by the aggressive Athenian expansion around the Mediterranean. Sparta attempted to draw Athens, a perennial naval power, into a land battle. Despite several Athenian successes at sea, Sparta continued to provoke Athens into a land battle by twice invading and devastating Athenian property in the country. Sparta’s actions caused the Athenians to turn on Pericles. Nevertheless, Pericles remained steadfast that victory would be achieved if they upheld the objective of defending within the city walls and defeating the Spartans at sea.

The word ‘strategy’ is of Greek origin, and according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, it means ‘a careful plan or method’ to achieve one's goal. Pericles understood the concept of strategy better than his contemporaries, and the Athenians reinstated his command, allowing him to expertly employ his tactics to meet Sparta in combat under advantageous conditions. Likewise, investment strategy is the means one uses to achieve investment objectives. A sound strategy must account for unknowable investment risks and remain the central long-term focus for any investor, as they attempt to distinguish between the market's signal and the noise. Pericles eventually earned credited as the mastermind of Athenian greatness, yet he did not foresee the terrible plague in 429 BC which weakened the city state and claimed his life. But as Pericles wisely counseled, "The key is not to predict the future but to prepare for it."

With kind regards,

St. James Investment Company

[1] Adam Wernick and Annie Minoff, “Science Friday,” The World, July 14, 2014.

[2] Gunjan Banerji, “Amateurs Pile Into 24-Hour Options,” The Wall Street Journal, September 12, 2023.